27 years of Half Ton designs

THE EVOLUTION OF OUR HALF TON DESIGNS FROM 1966 to 1993.

I have been fortunate to have had the opportunity to design yachts aimed at the Half Ton rating limit from the very beginning to the very end of the Half Ton era, but until now I have never looked back at this collection of designs to see what they have in common, other than being Half Tonners.

Many of my fellow IOR designers have had tremendous successes in this sphere of design and some, having produced winning boats, have adopted a theme and/or strategy of steady development in their ongoing work.

Looking at my own efforts now, through the prism of reflection, I wonder if my apparent scattergun approach to a supposedly ‘level’ problem was the right one. This journey of trying to remember the why’s and wherefore’s of design processes has been a head scratching time. I hope you enjoy my ‘logic’, as best I can remember it!

A key driver of any race boat design project, however, is – ‘just how much of a race boat is it going to be’? If the answer is pure, no holds barred race machine, then the answer to that question is clinical and simply comes down to the designers interpretation of the rule and the expected conditions of the primary event. If however the design is to be coloured by a dual purpose role and or fulfilment of production building techniques, the answer is anything but clinically pure.

Some of these 14 designs of mine, covering 27 years, fall into the pure race boat slot while others are heavily influenced by a dual purpose requirement. There is a third category too – which is the ‘I don’t give a damn about the rule – let’s just design a fast boat’.

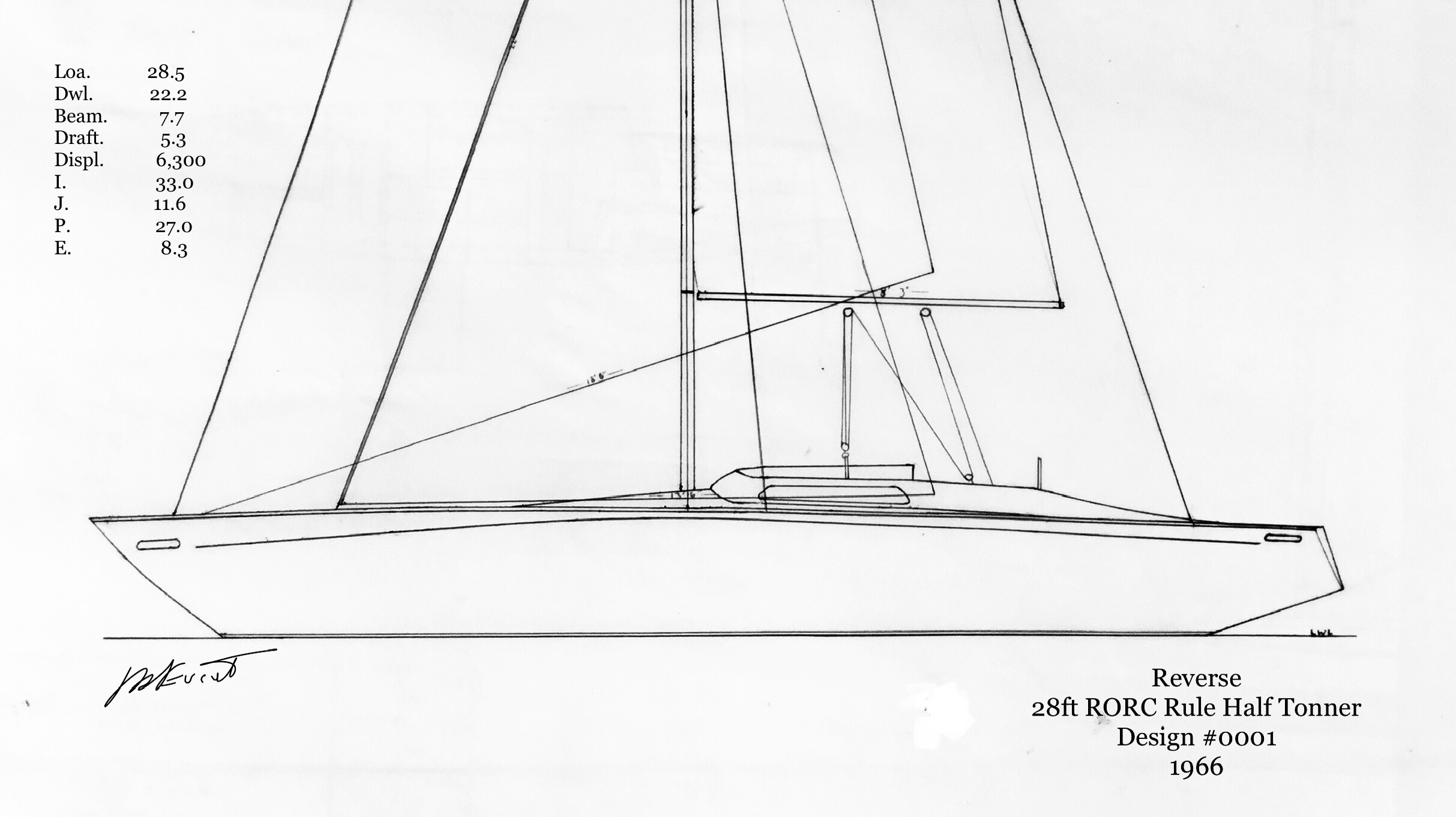

REVERSE is our 1966 offering. Designed to the RORC rule she is pure racer. Totally inspired by Illingworth and Primrose with a little van de Stadt thrown in on the spade rudder department. I was surprised, looking back, just how narrow the design is and by the choice of wheel steering at the front of the cockpit- Outlaw style.

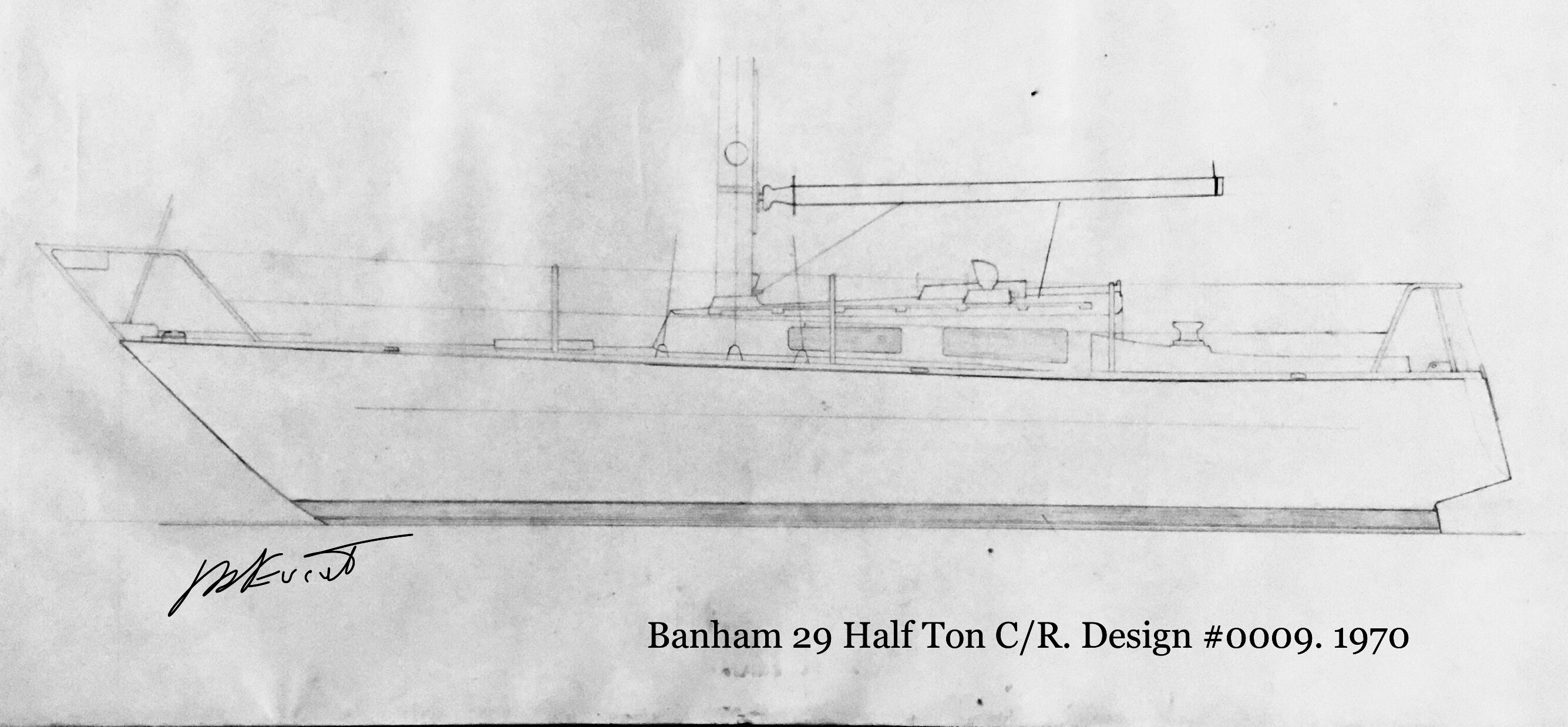

Our next design, the Banham 29, drawn in early 1970 is our first attempt to interpret the brand new IOR. But being a grp production design she is ultra conservative. A moderately heavy, short waterline boat with a big rig, the builders required a dual purpose boat with good accommodation. We managed to keep weight out of the bow, however, with an empty fore peak. Slightly against expectations, this design performed best in a breeze – probably due to a big lead keel, very firm sections and a wide waterline.

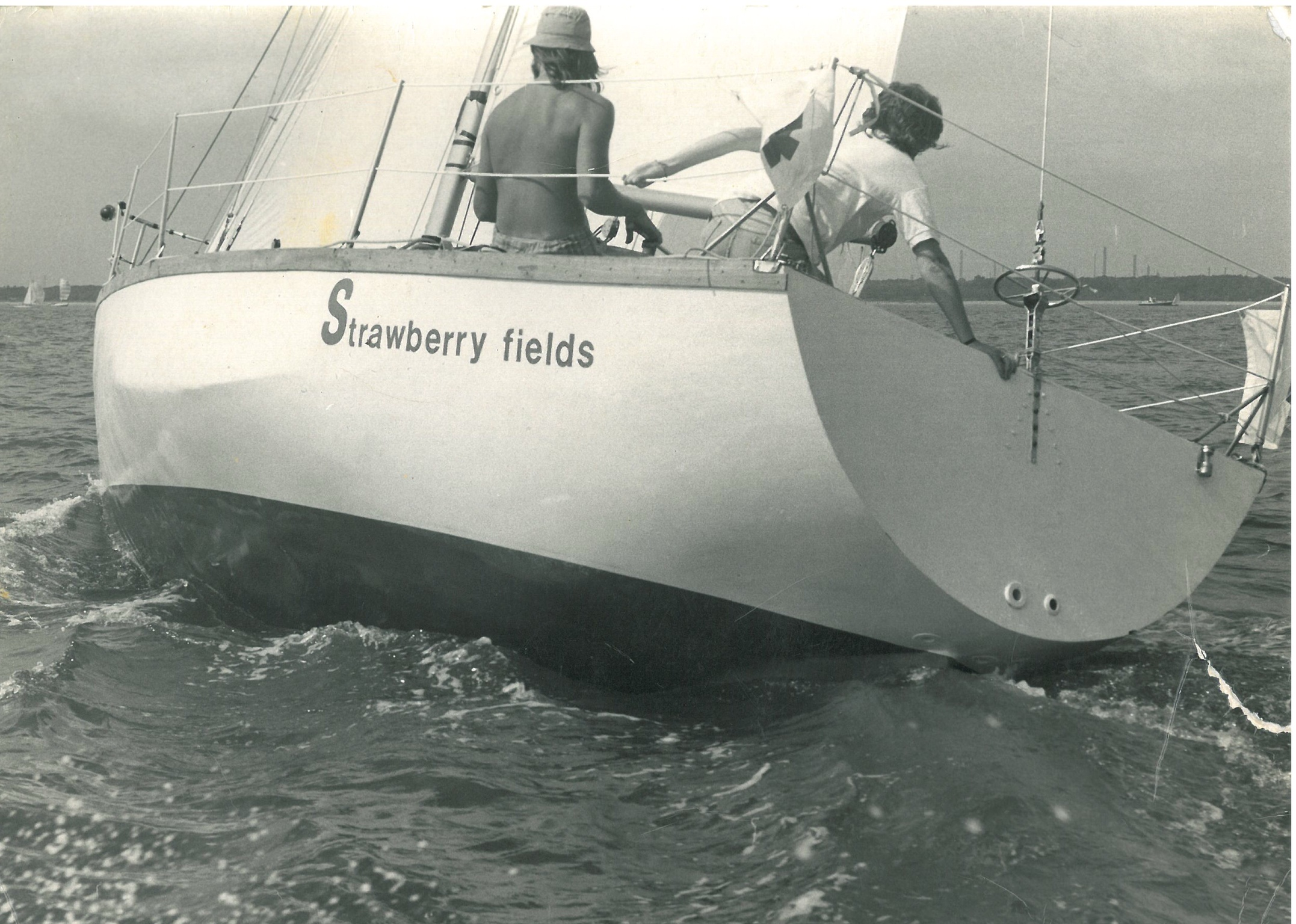

And then in 1971 came Strawberry Fields. A very different beast altogether from which three further designs were derived in quick succession. Strawberry Fields was the epitome of a racing machine. Completely empty from the mast forward, she had tubular alloy pipe cots set as far aft as possible, a minimal galley, a bucket for a toilet and no floorboards. To get down below you dropped through a hatch in the bridgedeck. There was no companionway hatch or steps or even fore hatch. All too heavy. Storage below was exclusively courtesy of store bought plastic bins!

I poured over the, still new, IOR rule book for hours developing her lines and came up with, what I believed at the time, was a unique double hull form aft of the keel extending aft almost to the transom. It was designed to have the same effect as the bustle developed by Sparkman &Stephens, but instead of being faired in with distorted buttock lines it was more canoe shape grafted onto the bottom of a shallow main hull. It’s main purpose, however, was to get displacement aft and to trick the measurement rules into thinking the boat had a shorter sailing length than it actually did. The effective ‘measured’ length equated to a waterline of 23ft, but in reality the hull extended nearly two feet further aft. This together with a very wide full stern gave the design a very long sailing length albeit married to a short overall length. The bow is ultra fine with max beam well aft. In order to extract the most out of the measurement points we adopted a chine amidships combined with an almost bizarrely narrow waterline. After the plug was constructed, rule changes made to IOR cost us dearly in regard to the chine and the ultra narrow waterline, so when she was launched in early ‘72, we had to slice a fair amount of sail area out of the genoas. She did prove to be an excellent heavy air boat, but certainly lacked upwind and downwind area for light airs.

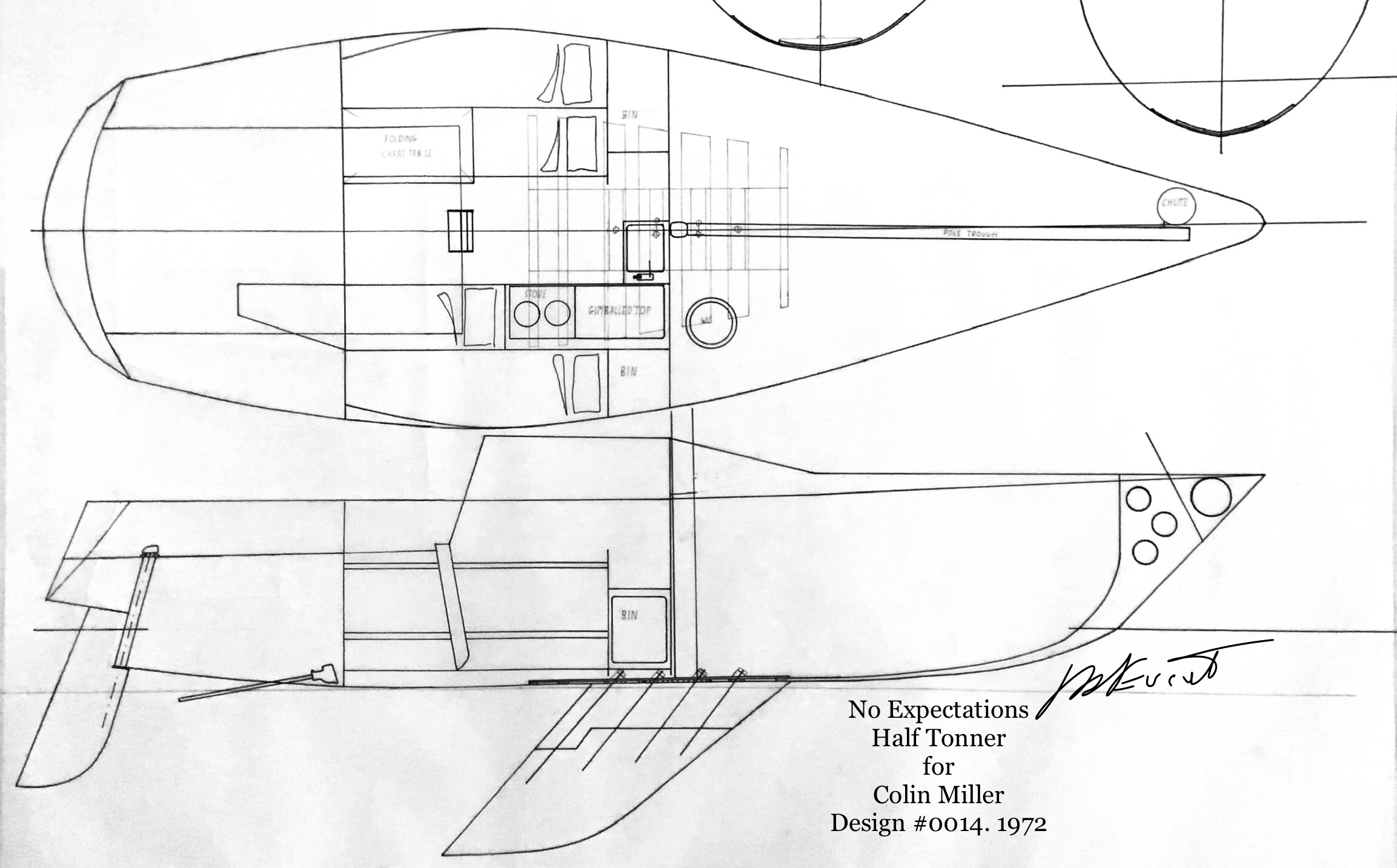

After the rule changes hit us so hard we did a follow up boat, No Expectations, and addressed the chine ‘ penalty’ by running it right aft to the transom. That technically made it a hard chine boat so we could keep the beam measurement right to the edge of the chine. There was nothing we could do however about the waterline beam problem, but we did extend the waterline back even further by bringing the rudder up from underneath the bustle to behind it. It seemed to work pretty well, but as is so often the case the two boats never sailed against each other. In fact that is a historical element of this entire half ton development. I know of no situation where any of these designs have sailed against each other!

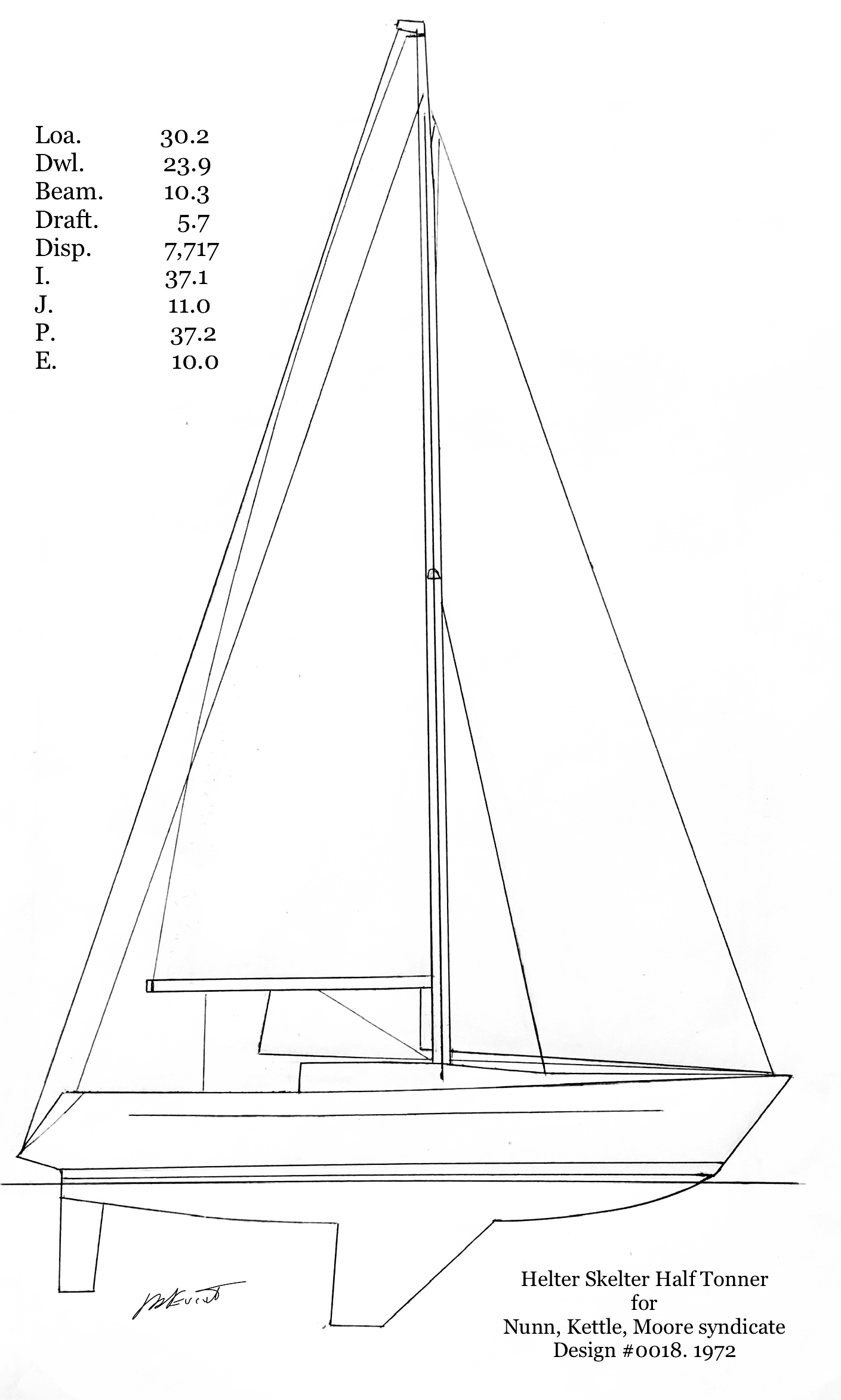

Helier Skelter in ‘73 was arguably more rule friendly. We gave up on the chines and narrow waterline, but kept the superfine entry, full stern and beam aft shape. The bustle became a bit more conventional and the displacement went up considerably so we could gain some sail area. It was our first foray into fractional rigs too seeing that you could gain ‘free’ sail area under the rule. Once again she was completely stripped out and the high freeboard allowed the deck to be almost flat with no coach roof.

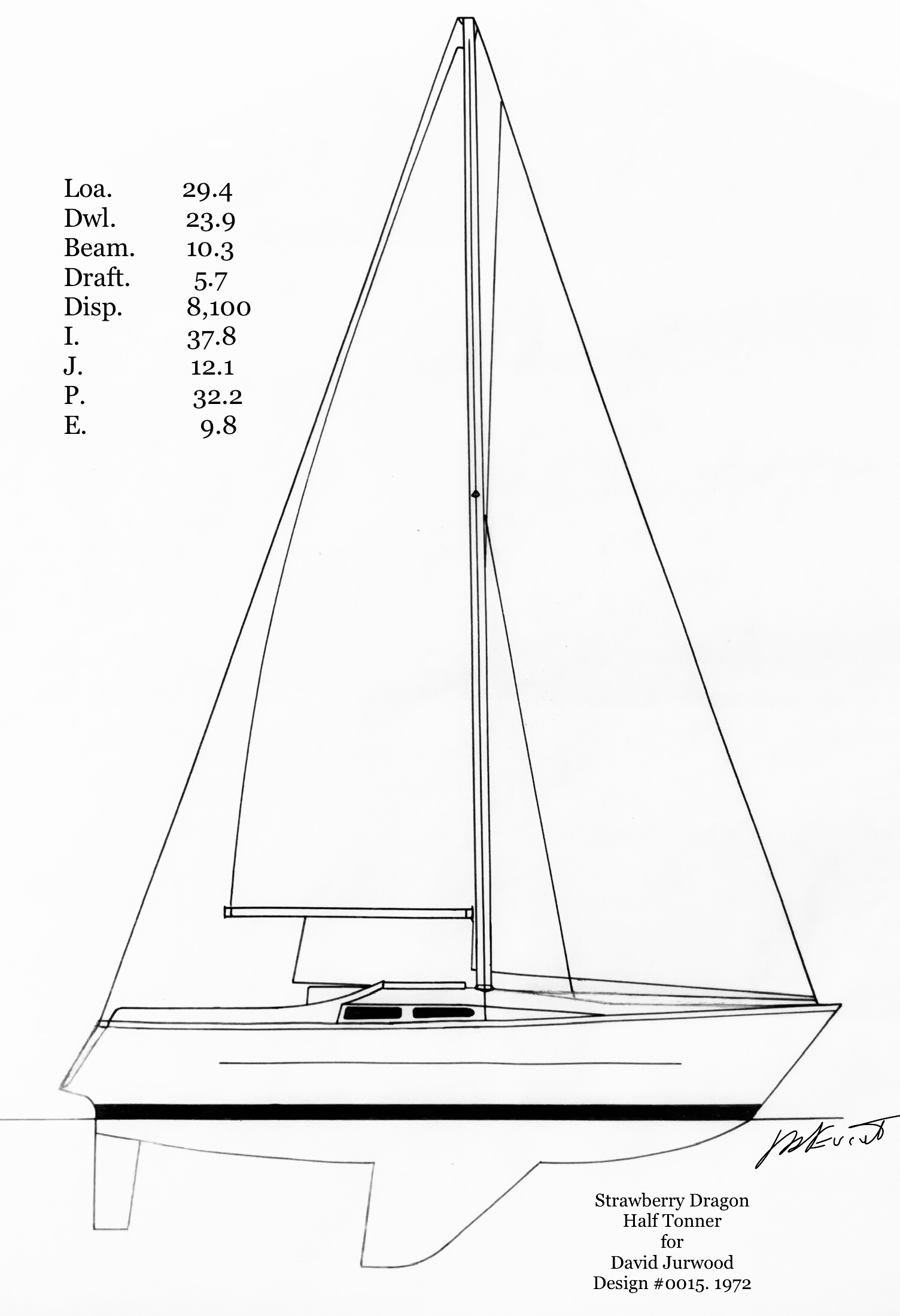

Strawberry Dragon was essentially similar, but with a fully fitted interior, coach roof and displacement increase to match. We also pinched in the stern a little bit for reasons I cannot remember! Later in life this boat cruised half way around the world and now lives in Australia.

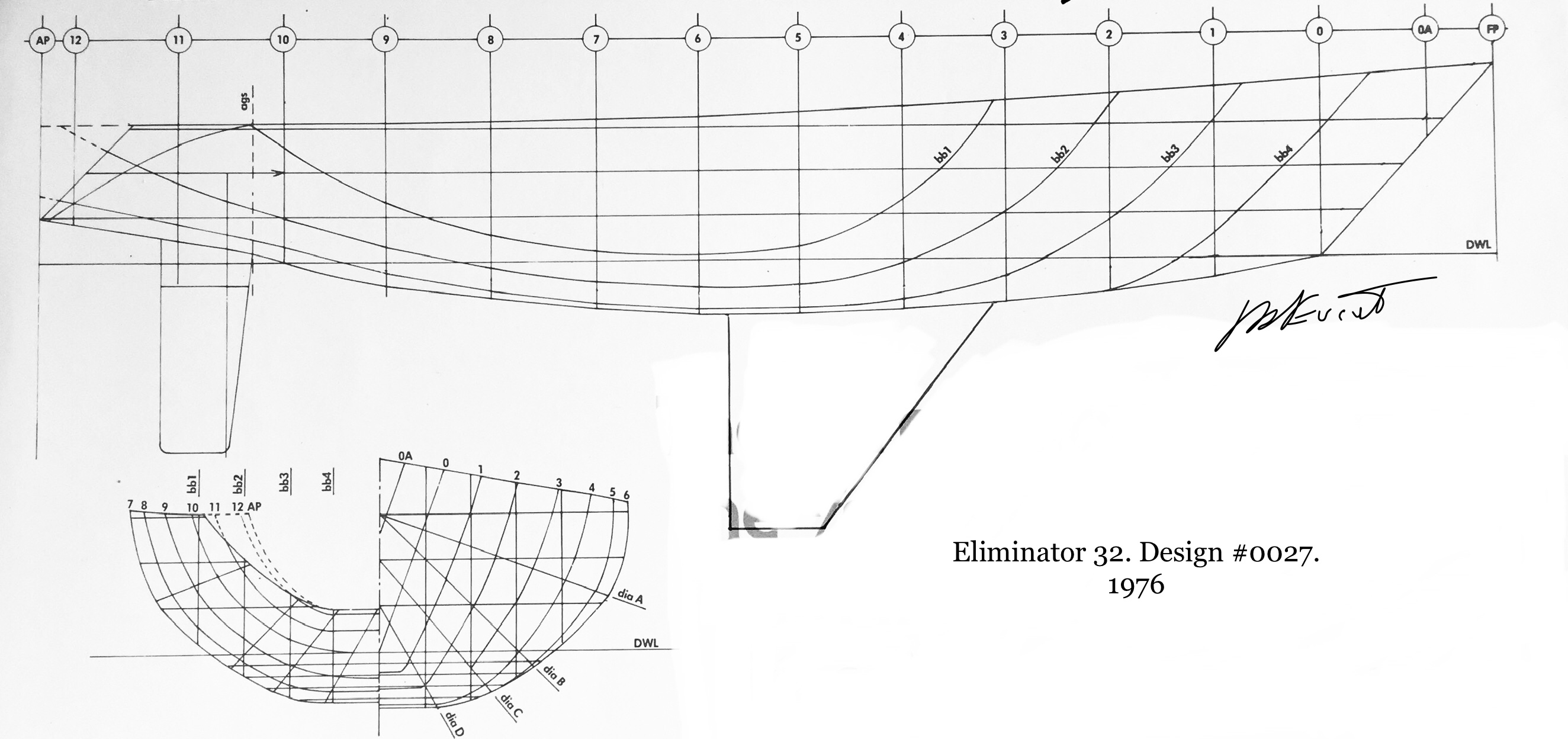

In 1976 we drew the Eliminator 32 for E Boat builders Production Yachts. Hull wise the Eliminator was created to get everything out of the fast changing IOR, but in reality when you give a high volume hull to a production boatyard they want you to fill it with interior. We tried all the tricks to get the best of both worlds with all the primary berths aft and the galley, chart table and engine forward, but it all still weighed a lot and virtually all the owners plumped for the fully lined interiors and Treadmaster on the deck. Rating this dual purpose cruiser/ racer configuration fairly was where IOR really fell apart. The fitted out boat weighed 20 per cent more than the designed stripped boat and yet the rating was higher! It was impossible to explain this ‘logic’ to the bewildered owners. The fitted out Eliminator’s did eventually have their glory days, but not until the advent of CHS and IRC. Our choice of extreme fractional rig with giant mainsail and very short foot headsails didn’t help either – particularly as we elected for an ultra simple single spreader, runner free, swept back rig. The sailmakers and sailors were struggling to get the best out of the set up for upwind performance. Team Sails got the hang of it though taking an Eliminator to an overall win in the Tomatin Trophy.

We also pushed the rule hard in the hull shape department with billiard table flat sections running from stem to stern, lots of beam, narrow waterline, wide, flat stern sections and only minimal distortions around the aft girths. Under IOR the design really came into its own when stripped out below and fitted with a no compromise rig complete with runners, checkstays and in-line shrouds.

The design was further developed in 1979 with Existential using the hull and deck mouldings from the Eliminator, but extending the stern to give a truly massive overall length of 34ft. Needless to say this ‘freebie’ only survived for two season of IOR racing. In common with the Eliminator the forward waterlines are completely straight giving a fine entry.

Our first ‘non-rule’ Half Tonner was Eagle in 1978. This was a deliberate attempt to take the Eliminator concept , but take out the rule inspired flats. We made the bow even finer and veed and the stern as full as possible. To ‘pay’ for this in IOR terms we went for virtually no overhang at the stern and a transom hung rudder. Once again a fractional swept back spreader rig was employed. This basic design went on to be very adaptable with daggerboard, lifting keel, long keel and even winged bilge keels. As an IOR Half Tonner I don’t think the theory was ever tested. Looking back now the design philosophy had much in common with the S&S designed Columbine of 1972. I suppose this is how influences creep into designs.

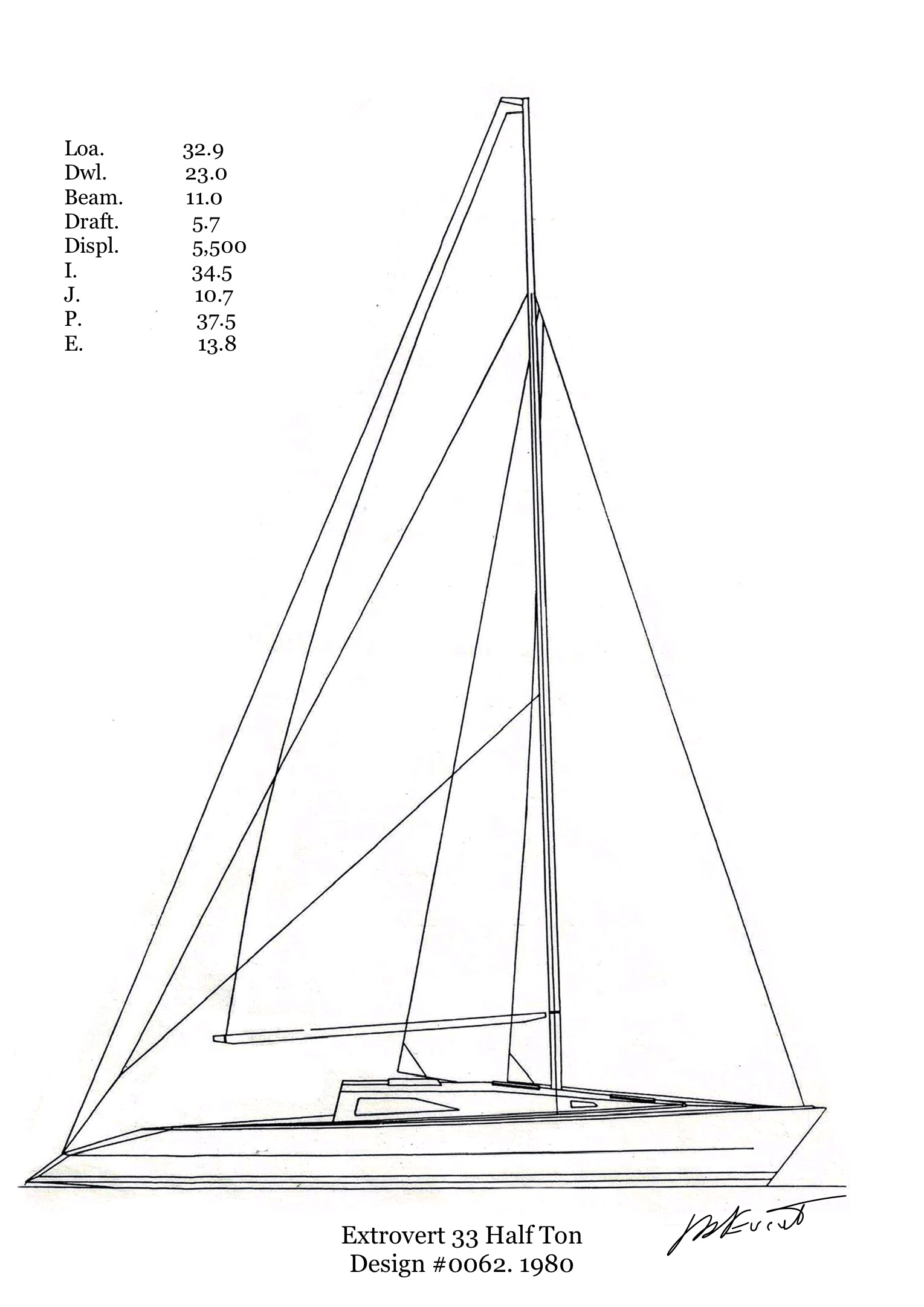

Probably our biggest rule pushing Half Tonner was the 1980 Extrovert 33. Intended as an aluminium semi production boat, a couple were also built in plywood. The multi chine shape is perfect for exploiting the measurement points in IOR and we pushed the measurement points around the stern with a big crease that we had used very successfully on the mini ton Silver Dream Racer.

In 1980 we also developed the Grace design for an Italian builder, but this was very different again as part of the brief was to make the design road legal for towing so the beam was limited to 2.5 metres. Also required by the builders was a fitted out interior and lifting keel and rudder. This concept was quite a challenge and in order to help it rate Half Ton we looked once again at the double hull design aft ( previously seen on No Expectations in ‘72) to give maximum sailing length with minimum measured length. As the boat is light, long and narrow, the rig is necessarily small, but effective.

The North 26 (actually just under 27ft long) was drawn in 1981 with only half an eye on the rule. She was to be ultra light, ultra fair and capable of planning. We just made sure the IOR measurement points fell on the chines and pretty much left everything else to take care of itself. As an IOR racer it pretty much proved that a boat like this can win, but it’s impossible to make an all rounder IOR boat without exploiting all of the idiosyncrasies of the rule.

Next up in 1982 was our Half Tonner for racing on the Arabian Gulf – hence the name – Gulf 30. This is unashamedly a light air design. Light displacement, short waterline and big rig. The high cg keel is to help with weight concentration necessary in the ‘sloppy’ seas of the region. For good performance in a breeze the stern is full, but in this design it is balanced with a fuller bow to help reaching and running speed.

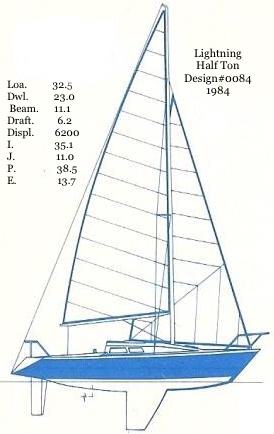

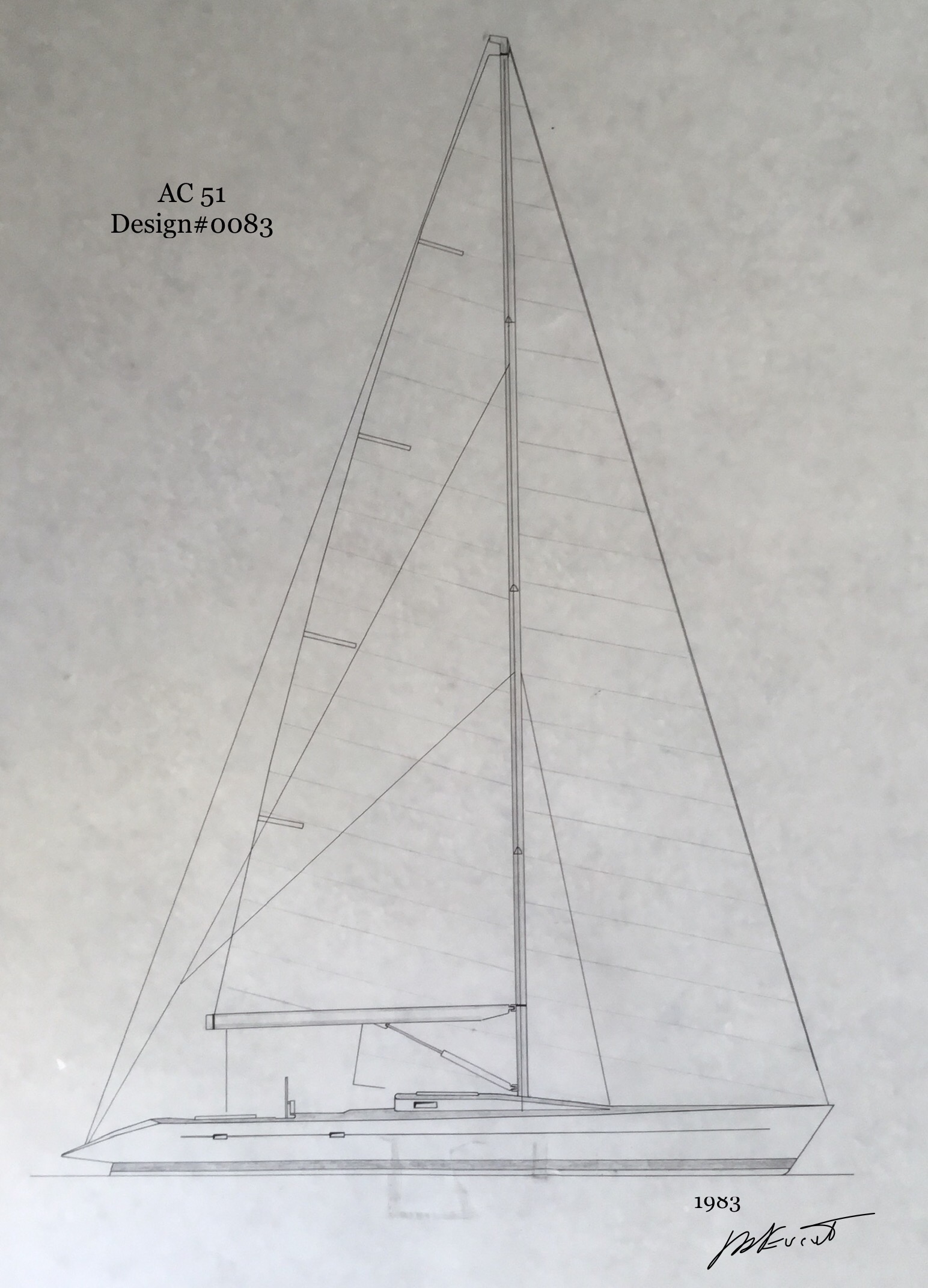

In 1985 came Lightning – basically a development of our Eliminator design which we still felt had plenty of potential. The main differences in the design were in the bow area where the sections were much softer.

Our final tilt at an IOR Half Tonner came right at the end of the IOR era in 1993 with Platinum. It was slightly tongue in cheek as the owner’s primary interest was to race JOG and this series had, by then, gone over to CHS. We decided to make the key points of the design work as a CHS racer, but to keep the overall package within certain IOR parameters. This meant, for example, employing a small bow overhang – upright bows rate very badly under IOR, a combined fractional (for IOR) and masthead ( for CHS) rig and interchangeable keels – one low cg and one shallow IOR keel.

And so the journey came to an end with the demise of IOR in 1994. I hope you have enjoyed this summary. It made me realise that there was potentially so much more ‘story’ per boat, but that will have to be for another time! I hope the drawings I have selected make sense with the words!

0

0

Admiral’s Cup

Science v nature

An emotive picture for sure. The dolphin reflecting the power and beauty of mother nature , the young woman peering over the lifelines at the horizon representing our futures and the bright orange razor edged foil depicting science and technology and its rightful place in our world. But as with every story there is another, possibly sinister, side to this picture. Quite literally, in this case, on the port side running just under the water is the other foil developing lift and speed scything silently through the ocean at speeds in excess of 30 mph. Now the dolphins, sharks and killer whales have another challenge to their domain from humankind. Maybe over time they have learnt to stay away from propellers, but this is a whole new level of potential threat travelling at hitherto unimaginable speed. And it’s not just impact injury the aquatic world may have to deal with. These foils, with their upturned ends, have all of the appearance of daggers ready to tear into the soft underbelly of any unsuspecting creature. It is to be hoped that this laudable mission to raise awareness of climate anomolies isn’t hijacked by an unfortunate meeting of nature and technology.

Science and nature

An emotive picture for sure. The dolphin reflecting the power and beauty of mother nature , the young woman peering over the lifelines at the horizon representing our futures and the bright orange razor edged foil depicting science and technology and its rightful place in our world. But as with every story there is another, possibly sinister, side to this picture. Quite literally, in this case, on the port side running just under the water is the other foil developing lift and speed scything silently through the ocean at speeds in excess of 30 mph. Now the dolphins, sharks and killer whales have another challenge to their domain from humankind. Maybe over time they have learnt to stay away from propellers, but this is a whole new level of potential threat travelling at hitherto unimaginable speed. And it’s not just impact injury the aquatic world may have to deal with. These foils, with their upturned ends, have all of the appearance of daggers ready to tear into the soft underbelly of any unsuspecting creature. It is to be hoped that this laudable mission to raise awareness of climate change isn’t hijacked by an unfortunate meeting of nature and technology.

British Steel 71 Ketch

Sometimes there are designs you would like to revisit if a new similar commission came along. This 71ft steel ketch is one of them. I like the idea that it is steel. It’s an unusual way to build a performance boat these days, but it’s a material that can be made to work and it make# for a very strong and economic build.

I like the rig. A fractional ketch with an equal height foretriangle on both masts so the offwind sails can be partially interchangeable. I like the fact that we have the mizzen well inboard.

The deck plan and interior work work for me too. Triple collision bulkheads forward. A great recreational see out area amidships with a secure galley. Sail stowage right aft with large deck hatch aft keeping the weight were you need, but the sails well out of the way of living accommodation. A completely separate aft nav station with its own entrance from the deck with easy communication to the helm and tactician.

All in all a product of a very good and specific brief but one which would work just as well today as it did nearly 30 years ago.

From Russia with Titanium

With Anglo/Russian ‘relations’ very much in the news I have been reminded of my times in Russia in the early nineties. And what fun they were! The newly revamped Moscow airport – still a dark and foreboding place. Being met by someone with all the credentials of an ex KGB spy – arriving half an hour late as his soviet era car broke down on the way to pick me up.

With Anglo/Russian ‘relations’ very much in the news I have been reminded of my times in Russia in the early nineties. And what fun they were! The newly revamped Moscow airport – still a dark and foreboding place. Being met by someone with all the credentials of an ex KGB spy – arriving half an hour late as his soviet era car broke down on the way to pick me up.

In the summer of 1992 my phone rang in my London office and a very well spoken ‘American’ sounding gentleman announced that he was from the Russian Embassy. “Why me” I asked a few days later when we met in a cafe across the road from the Embassy. “You were in the London phone book” he replied ” And your office is just down the road from here.” Turns out the Russians were looking for a way to turn roubles into dollars and I had, what I thought, was the perfect answer. In the Cold War era the Russians had quite a reputation for building war machines in alloy or titanium. I figured these skills could be used to good effect to build large yachts utilising the inexpensive Russian workforce and taking advantage of the huge currency differential. Turned out they liked the idea so a visa was duly arranged and I was flown out to Moscow – British Airways! That first trip, I had no idea what to expect. I was told I would be completely taken care of, but what transpired was some adventure!

Vsevolod Kukushkin introduced himself to me at the airport, not as an ex soviet era spy, but as a journalist who had travelled the world specialising in covering the Olympic Games since 1960. He spoke impeccable English so, on the long drive to my ‘hotel’ through Moscow and out the other side down straight roads through dense forest, I got pretty much the whole story of a Russian citizen ‘enjoying’ the freedoms of the west through the times of the Cold War. My accommodation for the duration of the trip was the original ‘gated’ community – a sanatorium for worn out Soviet officials, my host informed me.

My self contained ‘apartment’ was nice enough. The listening devices had all been removed, there was loo paper (a serious black market luxury I was to find out later) and even a plug for the bath! In fairness to my hosts they had in fact gone to a lot of trouble. The fridge was stacked with ‘western’ food. But there was no phone and definitely no ‘coffee shop’. “Make yourself comfortable – we’ll be back in the morning” the enegmatic Kukushkin said closing the door! I drew a bath before turning in – the water was muddy brown.

Late the following morning we were on our way back into Moscow starting an eerie tour of massive Soviet factories. One such, over a mile long – empty apart from hundreds of workers doing nothing that only 18 months earlier had mighty TU22M Backfire nuclear bombers rolling out the front door.

Next on the agenda was very different. An aerospace company called NPO Energia, designers and manufacturers of Sputnik – the very first space vehicle launched in 1957. A replica launch rocket stood proudly outside the factory. Inside, Yuri Gulyants, chief of production, showed us around a teaming work place full of ‘space-ships’. The surprise was they were mostly being made for McDonald Douglas. Cheaper, I guessed , than building in the States, but the beginning of a huge satellite industry. They were too busy to build yachts so we moved on.

Gennady Levenets, production director, showed us around the Myasishchev Design Bureau. Again full of people, but devoid of work. They had, for years, been making the M4 nuclear bomber, known in Russia as the Hammer and by NATO as the Bison.

They seemed the perfect place to build high spec aluminium and titanium structures. Maxi yacht hulls would be easy! It was a strangely desperate place though. All home grown military spending had dried up and these giant factories were reduced to making prototype toasters and the like, in a vain attempt to compete commercially with Morphy Richards. I was proudly shown ‘advanced composite’ facilities. It was laughable.

I spent a couple more days enjoying the delights of the sanatorium waiting for the quotes to come through for the hull and deck structures from the plane makers. Well if they ever thought they were going to compete on the price of toasters they were way out on the maxi’s. Palmer Johnson in Wisconsin could build them for less, I told the bosses.

Still, all was not lost. On the fourth day I was introduced to the man bank rolling the project so far. Turned out we were neighbours in the sanatorium. His ‘apartment’ was in another nearby block, but he hadn’t wanted to meet me until I had been thoroughly checked out. Now I was made supremely welcome at a family dinner, cooked by his wife. Much alcohol flowed, but it was only a short walk ‘home’ for me, A short walk I made much later, but a great deal richer. After dinner we had ‘retired’ to the study. A large room with shelving all around. The shelves everywhere were stuffed full of bank notes. Stacks of currencies I could only guess at. The bundle I was given was US dollars. The total amount in the room was unimaginable. His words to me would take on a significant resonance in years to come: “There are three kinds of bankers. Honest bankers, rich bankers and dead bankers”.

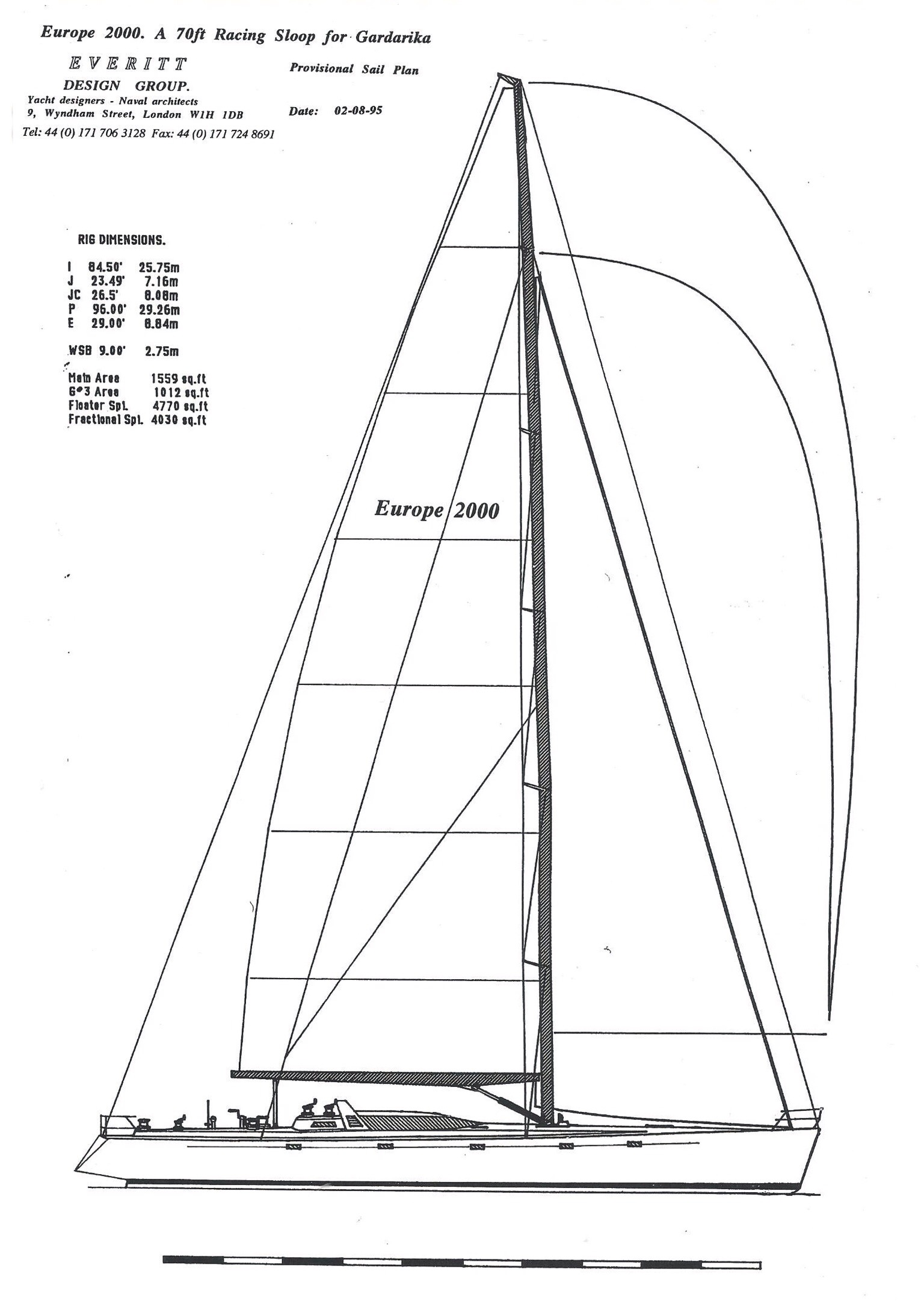

Safely back in the UK I set about ‘earning’ my fee. Basically I was tasked to create a plan to promote Russian diplomacy and technology to the world. Simple then! A round the world yacht race in 20 Russian built One Design 70 footers seemed like a good starting point. The race would start in St Petersburg call in on 23 countries around the globe and end in the Black Sea at Odessa. I worked up a budget to complete the programme for $94,000,000.

Meanwhile back in Russia having given up the idea of using the aircraft manufacturers, Vsevolod Kukushkin sourced two shipbuilders for us to visit. In October 1993 we delivered the provisional drawings and specifications and signed build agreements with Peter Domnin of Sointel Shipyard and Alex Mokskin of Lotos Shipyard to licence the building of twenty 70 footers.

But then, predictably, things went quiet. It was, after all, a pretty ambitious project. Roll forward a couple of years and we received our third invitation and visa to develop what had now become known as the Gardarika Europe 2000 project.

October 22 1995 we duly signed an agreement with Dr Alexandr Makarov, President of the Russian Investing Finnancial Club. Interestingly enough the Russian Finnancial Club is operating today in the banking and investment business.

Whatever happened to the three hulls that were completed for Gardarika, I guess I will never know. They looked pretty good when I made my fourth and final visit to Russia, but no requests for gear, rig or sails was ever made so it seems unlikely that they ever hit the water, but you never know!

As to the investment? Well it wouldn’t surprise me to find that loads of money, maybe even 94 million, was raised on the back of the yacht race to promote Russian Diplomacy and Technology to the World! Made me think of all that money I had seen back at the Sanatorium some four years earlier. Investment in Russia seemed then, and does now, like a code for something else entirely. A lot of dead bankers could attest to that if they could!

New Responsibilities.

Offshore racing yachts that can travel in excess of 30 knots bring new responsibilities to both crews and race organisers. But are the existing rules and the policing of them good enough to deal with the potentially deadly hazards of a Volvo 65, for example, charging through a mixed fleet of racing yachts at 25 knots. I know from experience that they are not. In Cowes Week last year, the Volvo 65’s along with some 100 footers were sent around the Island. They started early in the morning, but were charging thru much of the fleet in the Eastern Solent as they reached towards the finish at the Royal Yacht Squadron later in the day. I was racing aboard a Quarter Tonner on starboard tack doing just under 5 knots. Our fleet was virtually at right angles to the 65’s which were reaching on port tack at around 20 to 23 knots. In itself not necessarily a problem with plenty of sea room, but my five crew mates and I had the distinctly uncomfortable experience of Brunei hurtling towards us without wavering course at all. It was impossible to tell initially, from our very slow moving boat, whether or not they were going to hit us. Of course all we could do was hope they had seen us – little we could do to influence the outcome because of the vast differences in speed. What really bugged me about this, as Brunei blasted past our stern at ninety degrees to our course – a mere 10ft away was that nobody on Brunei made any attempt to show that they had seen us. The helmsman made no attempt to dip the bow a few degrees to demonstrate that he had seen us. To say they behaved in an unsportsmanlike manner is an understatement, but even more importantly they gave no allowance for the speed of their boat compared to the speed of the boats they were crossing, which could have very easily led to a disastrous T Bone collision. Worse was to come however from the Cowes Week race organisers. I reported the incident to the race office and was told to expect a telephone call from the Cowes Combined Clubs chief race officer. The call never came. And before you think that I should have protested and filled in a form, that was precisely part of the problem of mixed fleet racing with high and low speed boats that I wanted to discuss with the organisers. The protocols of conventional protests simply don’t apply in these circumstances. One day one of these high speed machines, driven by crews who fail to understand the limitations of much slower boats, will collide and kill someone. The rules, as they stand for events like Cowes Week, are simply not good enough.